The Central Council of Jews in Germany is renewing the call for a ban on the NPD, or National-democratic Party of Germany [Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands ]. Such bans have failed in the past, yet the Council is seeking to reactivate the urgency of this goal. To American readers, it may sound absurd to ban a political party you don’t like, so a little background helps explain the call: the NPD platform is based on xenophobia and scorn for what they deem non-German. As their charter describes, they are against the “Enlightenment-influenced Utopias and multiethnic excesses” of modernity. Like the Nazi party they emulate, they define enemies as those who don’t have the magical quality of inherent German-ness, enemies of “the Folk”; this, naturally extends to citizens of Turkish descent and Jews. Their followers perpetrate the waves of right-extremist violence that leave hundreds dead or injured annually and make certain areas of East Germany no-go zones for those who don’t look white enough.

But can you ban a political party just because what they say is trash and their influence is abhorrent? As Green Party political Volker Beck points out, “Banning the NPD won’t solve the problem of right-extremism. Their following would still be there and they would simply look for new forms of organization.” In addition to being ineffective, such a ban also risks admitting that the current democratic methods of combating hatred are ineffective: Heribert Rech of the Christain Democratic Union believes that “Party-banning-processes don’t get us anywhere; we must fight the NPD politically.” Finally, others claim that such a ban would lessen current awareness of the NPD’s actions, even if it eventually failed, only strengthening the party.

These claims are all wrong. While banning the NPD won’t solve right-extremist violence, it will stop its condoning and legitimization from a political party that has recently made its way into Parliament and sits on many local councils. Forty-three thousand Berliners voted for the NPD in the last elections this fall; these are lost votes that should have gone to parties that want to use public funds for social benefit rather than hate. The more money is used to promote a philosophy of xenophobia, the more “okay” such destructive thinking becomes. It is an ignoramus' answer to East Germany's high unemployment (in some places, 25%) but it works when trumpeted loudly enough and in the right tone by men in suits who have the legitimacy of the political arena behind them.

These claims are all wrong. While banning the NPD won’t solve right-extremist violence, it will stop its condoning and legitimization from a political party that has recently made its way into Parliament and sits on many local councils. Forty-three thousand Berliners voted for the NPD in the last elections this fall; these are lost votes that should have gone to parties that want to use public funds for social benefit rather than hate. The more money is used to promote a philosophy of xenophobia, the more “okay” such destructive thinking becomes. It is an ignoramus' answer to East Germany's high unemployment (in some places, 25%) but it works when trumpeted loudly enough and in the right tone by men in suits who have the legitimacy of the political arena behind them.Claims that an attempt to ban the NPD would draw attention away from it are ludicrous at their core, and one wonders which of the non-NPD politicians who consistently condemn extremist violence and xenophobia would feel justified in shutting up if the NPD no longer existed. One must also look at the atmosphere in which the call for a ban comes: Germany has already banned Nazi-related emblems. In the sea of Hitler mustaches and “homeland” slogans at NPD rallies, swastikas remain out of sight because of the strict illegality of displaying one. Although Mein Kampf can be found at most Barnes & Noble’s in the United States with nary a raised eyebrow, it is notoriously difficult to find in Germany and even most libraries don’t keep copies available. Such a country refusing to ban a massive Neo-Nazi organization is dangerously strange.

Finally, resistance to the ban often revolves around the distasteful idea of censoring politics, but is the NPD a political party or a hate crime organization? No one would dare call the Ku Klux Klan a “political party” in the United States, although for years they controlled the South with a specific social agenda. A glance at the NPD charter reveals ideas familiar to Americans raised on the rhetoric of the Religious Right: the importance of (heterosexual) family, anti-abortion stance, and pro death penalty. Not surprisingly, women appear on the group’s website only as contact partners for senior citizens’ or family affairs. Yet far beyond such conservative-but-not-criminal ideology are passages that call for an end to the German examination of its Holocaust past: “We Germans are not a nation of criminals!” The website also contains an image of Germany showing its pre-1945 borders, encompassing much of Poland and all the way up to Kaliningrad. Its discussion of the danger non-German-ness poses to the mystical inherent German-ness of the people is deeply troubling: no platform should be built on fairy tales.

Finally, resistance to the ban often revolves around the distasteful idea of censoring politics, but is the NPD a political party or a hate crime organization? No one would dare call the Ku Klux Klan a “political party” in the United States, although for years they controlled the South with a specific social agenda. A glance at the NPD charter reveals ideas familiar to Americans raised on the rhetoric of the Religious Right: the importance of (heterosexual) family, anti-abortion stance, and pro death penalty. Not surprisingly, women appear on the group’s website only as contact partners for senior citizens’ or family affairs. Yet far beyond such conservative-but-not-criminal ideology are passages that call for an end to the German examination of its Holocaust past: “We Germans are not a nation of criminals!” The website also contains an image of Germany showing its pre-1945 borders, encompassing much of Poland and all the way up to Kaliningrad. Its discussion of the danger non-German-ness poses to the mystical inherent German-ness of the people is deeply troubling: no platform should be built on fairy tales.

This is not a group that should be allowed to wear the mantle of “political party” any more, or permitted in any way to participate in a democratic government. It is sad that the citizens have chosen such a group and that it cannot be defeated politically, as its growing numbers and influence attest, but the answer is not to continue to come up with self-contradictory reasons about why it should continue to appear on the ballot. Along with an NPD ban, educational measures to combat violence are needed, and sharp awareness of Germany’s problem with xenophobia must be maintained. We needn’t watch it continue to masquerade as a political platform, however.

Heribert Rech quote from "Neuer Streit ueber NPD Verbot," http://www.juden.de/.

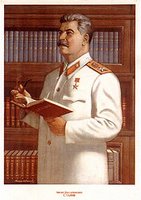

Top NPD rally image courtesy BBC. Other NPD images courtesy NPD Homepage.